The case for an archaeology of the ‘Jungle’

Sarah Mallet, a TORCH Knowledge Exchange Fellow based at the School of Archaeology at the University of Oxford and researcher for Pitt Rivers Museum's LANDE exhibition has been working with MOLA Post-Excavation Manager, Louise Fowler and MOLA colleagues on the Dzhangal Archaeology Project . Together they have been recording a group of objects collected by the photographer Gideon Mendel at the site of the Calais ‘Jungle’ camp, many of which were displayed in 2017 as part of his exhibition Dzhangal at the Autograph ABP gallery in London. In this blog she her reflects on the project.

Recently, the TV programme Years and Years, which takes place in a dystopic future Britain, showed the situation of migrants trying to cross the English Channel from France. The scenes were an unflinching look at the reality of illegal border crossings, and while it is supposed to take place in the near future, it bears a striking resemblance to current events. The unfairness of the situation is illustrated in all its absurd brutality by the presence of a British character amongst the group of displaced people. Even in a post-Brexit world, he can travel back to Britain relatively easy but choses to stay with the man he loves paying 6,000€ (~ £5,376) for them both to board an unsafe boat. I recently bought return tickets to go to France: it cost me about a hundred times less (£58) for a safe journey in a comfortable train.

Arendt describes in The Origins of Totalitarianism how racism and bureaucracy are interrelated, and nowhere is this more evident than at the borders of the Nation-State. While contemporary archaeology might seem like an oxymoron, archaeological approaches have increasingly been applied to the studies of modern issues. With this archaeological investigation of the material from the ‘Jungle’ refugee camp, we can favour an approach to understand the humanitarian crisis at the UK border in Calais that accounts for the longue durée political and social trends that led to 10,000 people living in a refugee camp in Northern France.

Through archaeological practices and methodologies, the Dzhangal Archaeology Project aims to use material culture to document the politics of exclusion and violence against displaced people at the UK border in France, but also the journeys undertaken and the networks of solidarity and resistance that were established between both countries.

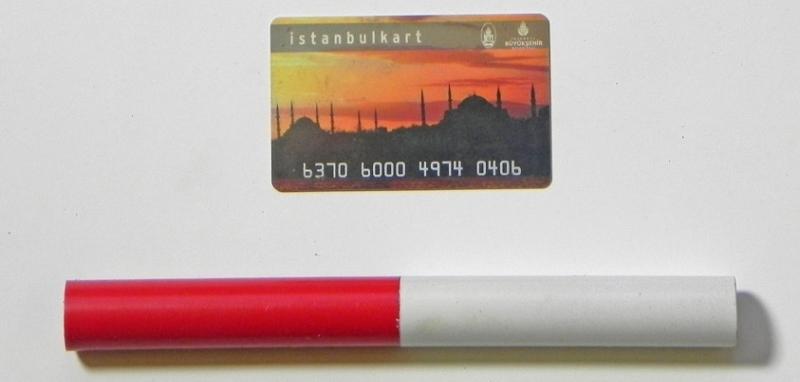

For example, a travel card for public transport in Istanbul found in Calais, or a biro bearing the name of the Italian postal service, ‘Gruppo Poste Italiane’ might be evidence of movement in the present, not unlike a Roman wine amphora in Britain can be evidence of movement in the past.

Contrasting with these ephemeral traces of passages through Europe is evidence of volunteers coming from Britain to Calais. Visibly ‘British’ artefacts, and particularly cans of beans and fish from British supermarkets, are a testament to the outpouring of help that came from Britain. These stories also need to be told: politicians claiming that people have had enough of immigration are hiding the truth of those who donated, volunteered and cared.

Some of the objects we have recorded also tell us of the violence at the border. Despite the French president’s claims that there are no police violence in Calais (E. Macron, Discours a Calais 16th January 2018), the material evidence to the contrary is overwhelming. We have recorded over 360 fragments of teargas canisters, ranging in date from 1993 to 2016 from two different French manufacturers (Nobel Sport and SAE Alsetex). The use of out-of-date teargas is not unique to France and has been documented in Egypt and in Venezuela, although there is no consensus on whether or not it is more dangerous. What is striking, however, is how the production seemingly increased in the years 2015 and 2016 (possibly evidenced by the presence of much higher batch numbers), and we are interested in investigating this further and see how this links to the situation in Calais.

This Knowledge Exchange Fellowship with MOLA complements my current project on the material culture of displacement. I work as a researcher at the Pitt Rivers Museum, where I have co-curated the exhibition ‘LANDE: the Calais ‘Jungle’ and Beyond’, which displays objects, artworks and photographs from the camp collected by refugees, activists and journalists wanting to bear witness to the situation at the height of the so-called ‘Refugee Crisis’. Working with MOLA on the Dzhangal assemblage is allowing us to contribute to an understanding of the camp, its residents, and those connected with it through the study of artefacts from the site. It is also allowing us to develop a reflexive approach to our methodologies for dealing with archaeological collections, as the wider Lande project reflects on the role of anthropological museums and collections in the 21st century.

The outcome of the Dzhangal Archaeology Project is to document the undocumented present, through the creation of a unique body of material and visual testimony to the lived experience of a European refugee camp in a hard border landscape. This collection, and the work around it, highlights the ongoing situation for refugees in France, and explore the status of the ‘Jungle’ as a place of protest, of conflict, of hospitality, of migration, of memory and of continued urgency. As conditions in Calais are currently worsening for displaced people (Help Refugees, 2019), we hope that our impact will be in raising awareness of this humanitarian crisis.