A one-in-a-mill-ion find - uncovering a medieval mill on the A428

All along the National Highways A428 Black Cat to Caxton Gibbet improvement scheme, we have uncovered ancient ways of life, work, and even play. One outstanding recent discovery with an incredible wealth of finds is the remains of a medieval (AD 1066-1485) windmill.

To celebrate National Mills Weekend 2024 on Saturday 11th and Sunday 12th May, we wanted to share what makes this a one-in-a-mill-ion find!

Location, location, location...

Our windmill once sat on high ground surrounded by farmland. Imagine how this would have looked in the medieval period, with the mill’s huge sails swooping over fields of wheat, barley, and oats. The local community would have grown their grain in large open fields, which belonged to the lord of the manor.

Who’s who at the medieval mill?

Owning this mill would have been a great position of power for the local lord of the manor. He received money for the flour sold, as well as rent from his tenants (the villagers), who did all the farming for him. 10 percent of everything they made was paid to the other centre of medieval society – the church.

This place would have needed a skilled miller. Working in a medieval mill was hard, with a lot of danger, as well as long hours! Windmills might look pretty from a distance, but there was a risk of injury from the heavy machinery, collapse during a storm, and fires…

That’s right - flour is flammable and even explosive! Millers had to be careful, as grinding for too long could heat up the flour and cause a fire in the wooden mill.

The Medieval Windmill

Our mill building had large central post, which could be turned so the sails always faced the wind. The post of the mill was partly buried in a big mound of earth to support it, making it a sunken type of Post Mill. These were first kind of windmill in Europe, dating back to the 1100s-1200s.

The miller poured heavy sacks of grain into the hopper, which fed the grain between the two millstones. The top stone, called the runner stone was moved by gears. These were attached to the central post of the windmill, and turned as the sails span round in the wind. The bottom bedstone didn’t move. Both had grooves that trapped and cut the grain, slowly grinding it into flour.

Did you know the two millstones never actually touched? The miller adjusted the gap between them – the smaller the gap, the finer the flour.

The excavation

None of our mill survives above ground, and the mound it stood on was levelled for farming. When we removed the topsoil to start our dig, all you could see of the windmill was the outline of the moat ditch that once surrounded it.

We began by excavating small post-holes on the land inside the moat. These would have held posts that were part of the main mill building.

Then we started work on the huge moat ditch. When we excavated ditches like this, we usually cut trenches called ‘slots’ into it, rather than excavate the whole ditch in one go. Our largest slot was over 11m long, 3m wide and 1.5m deep! It took many hours and archaeologists working as a team to dig and record this immense ditch.

Why did a windmill have a moat?

This was not unusual in the medieval period, especially with this ‘sunken’ type of mill. The soil from the ditch was a vital part of the mill’s construction. It was piled high into a mound so the mill sails could be raised higher into the wind.

Because this area is naturally very wet, the deep ditch would have collected water and become a moat. We could see evidence for this during our excavations because it was full of shells from water snails!

What did we find?

We found lots of different things that had made their way into the moat, which filled up with silt over the years. The erosion and flattening of the mill mound added more material to the ditch.

Our finds included:

- Lots of pottery sherds, including beautiful medieval green glazed ware

- Animal bone

- Over 100 iron nails, likely from the wooden windmill building

- Metal farming tools, a horseshoe, a scythe, and a possible coulter (blade) from a plough

- Personal items including shoe or belt buckles

- Clay tobacco pipe stems, from the post-medieval period

La pièce de résistance – 17 pieces that is!

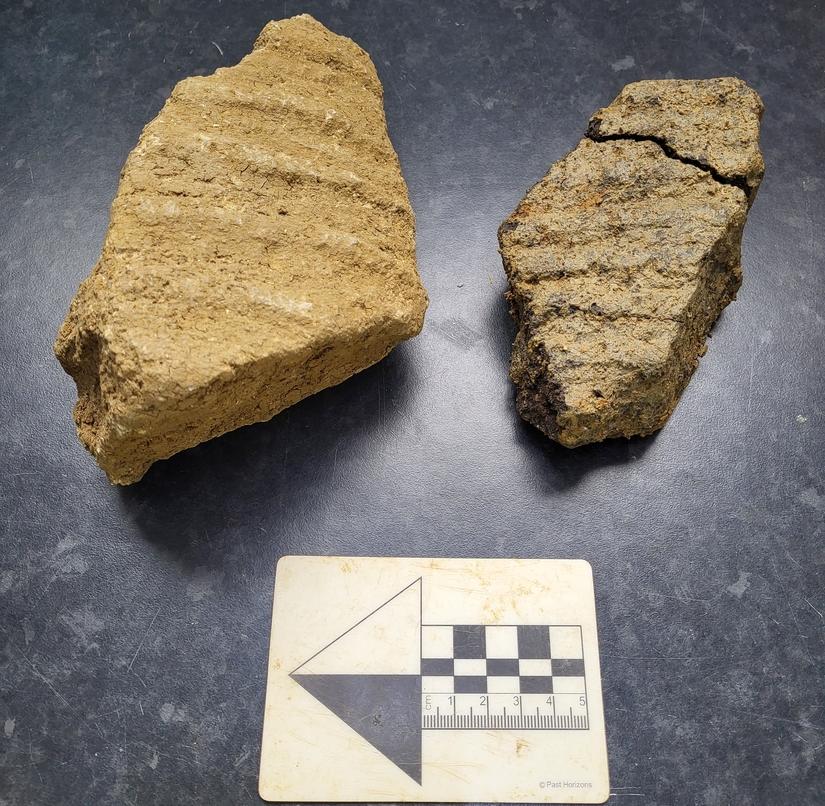

Also in the ditch, we found 17 pieces of millstone. At the bottom of the moat was a dark ‘lava’ millstone. This type of stone was imported from Mayen in Germany and was very popular for milling because it has a very rough surface – caused by bubbles forming in the cooling lava.

You can see our stones have been ‘dressed’ (carved) with groves to catch and cut the grain.

In the same ditch, we found another type of millstone with a much finer, harder surface. This probably replaced the ‘lava’ millstone.

What’s next?

Our excavation of the medieval mill has finished but work to process and study all our finds is ongoing, so watch this space!

In the meantime, why not visit the oldest surviving windmill in England and get an idea of how our medieval mill might have looked! Just south of the modern A428 near Caxton is Bourn Windmill which was built in c.1513-1549AD.

By Calypso Finch, Archaeologist and Digital Engagement Assistant on the A428.

JOIN US ON OUR JOURNEY!

#A428BlackCat

Find out more about the A428 National Highways scheme

Excavations are being undertaken by archaeologists from MOLA as part of the National Highways A428 Black Cat to Caxton Gibbet Improvement Scheme managed by Skanska.