Park Street and the Coffin Industry

Josie Wall works at the Coffin Works Museum, which is run by Birmingham Conservation Trust, as Operations and Volunteer Assistant. Josie’s particular interest and area of expertise is Victorian funerals and the garden cemeteries that opened outside cities in the 19th century.

In this blog she explores Birmingham’s legacy as the centre for coffin furniture manufacture and reveals the historical context of some of the archaeological discoveries unearthed by our archaeologists at Park Street burial ground for HS2.

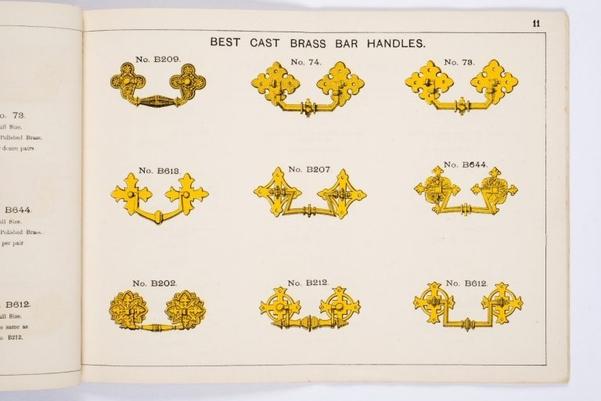

The Coffin Works is a unique museum in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, which preserves the Newman Brothers’ Victorian Manufactory as a time capsule. The factory opened in 1894 and from that time the Newman Brothers specialised in making coffin furniture, in particular high-quality cast brass coffin handles.

Although the factory dates to just after the closure of Park Street burial ground in 1873, the staff and volunteers here were all very excited to see what would be found during the recent excavation at the site. The types of coffin furniture recovered there would be very similar to those in our earliest 1890s catalogue because funeral fashions stayed consistent for quite long periods.

Coffin furniture, or coffin fittings, is most easily described as all the metal decorations added to coffins, including handles, breastplates (where name and dates are shown) and any other elements such as lid motifs, corner clips, nails and screws.

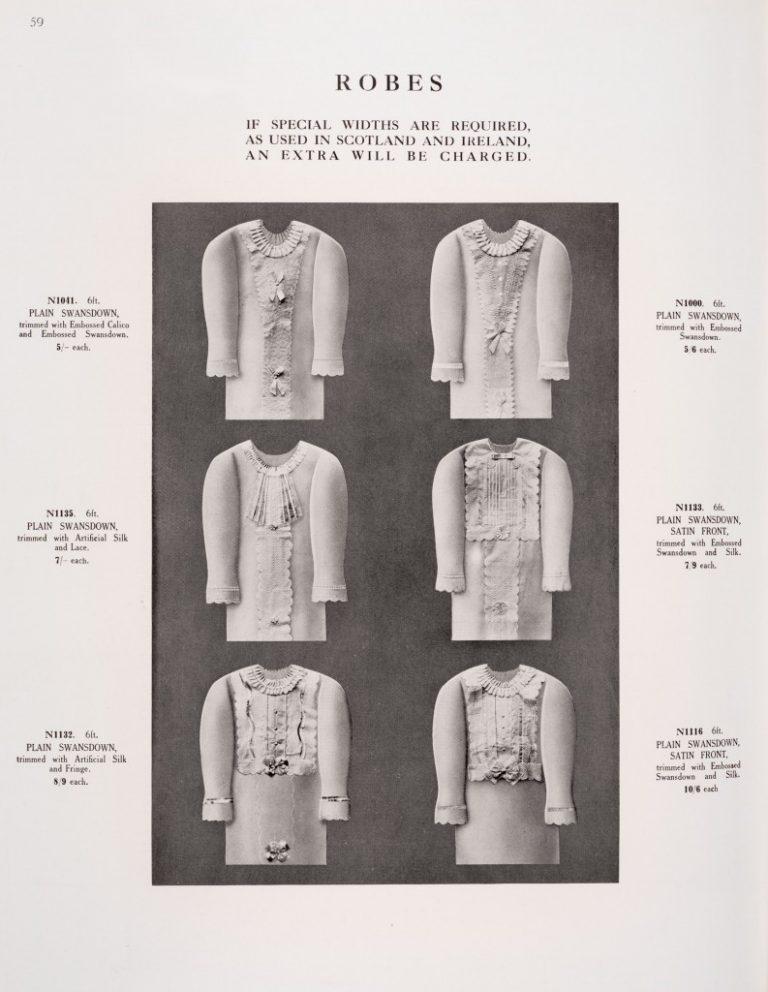

The Newman Brothers also made the ‘soft goods’ for coffins, including coffin linings, pillows, mattresses and shrouds. We know this as they advertised for seamstresses as early as 1911. Again, they would have looked similar to those buried at Park Street, because shroud designs didn’t change substantially until the 1950s.

Another reason for our interest is that the Newman Brothers were relative latecomers to the coffin furniture making business – by the time they entered the trade, Birmingham was already the centre of manufacturing for these items, as it was for so many small metal goods. Birmingham-made coffin handles were used around the world, particularly the British Empire. The coffin furniture found at Park Street would have been locally made, and perhaps some of the people buried there were even employed in the industry

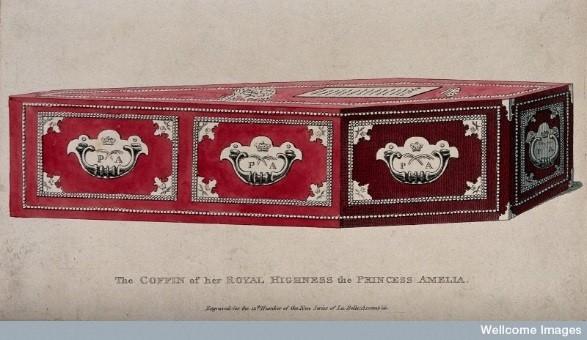

At the time Park Street opened, a coffin for a rich person would have looked something like this:

This type of coffin was made from wood, usually Elm, and then covered with fabric. Black or red velvet were used for the most expensive coffins. The fabric would be held in place by rows of decorative nails – the more nails, the more expensive it was! There would also be decorative metal elements on the coffin; the handles were very ornate and there were three pairs down each side of the coffin. There might also have been ring handles on the head and foot ends of the coffin because these coffins were usually ‘triple shell’, which means there was an inner and outer wooden coffin, with a lining made from lead in between, and so were very heavy.

The lid of the coffin had a large breastplate where the name of the deceased and their date of birth and death could be engraved or painted and decorative motifs added – often with religious or sentimental symbolism. One very popular set was the Urn and Glory – we have examples here in our collection but this design was popular from the 18th century until the 1960s.

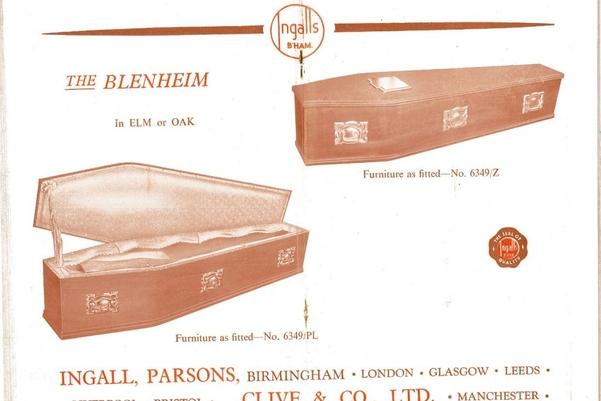

In the late 19th century a coffin for a rich person would have looked more like this example. Instead of Elm covered with upholstery, French polished oak coffins were now the most fashionable. These coffins were often lead-lined too. Solid cast brass handles were used on the most expensive coffins. A set of six handles would have cost 15 shillings in the 1890s – about the same as a week’s wages for a clerk, so they were very exclusive products.

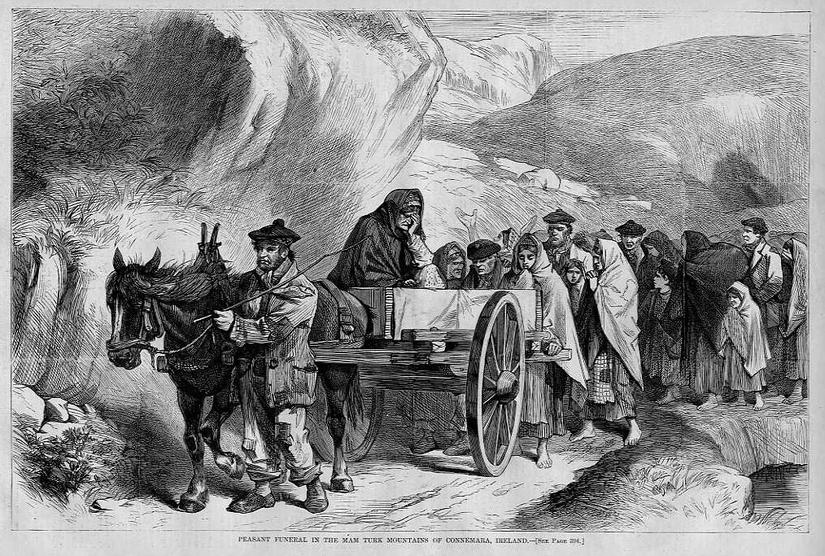

The coffin of a poorer person in the 19th century would have been a much simpler affair; made of plain wood, without a lead lining. The wood used would have been cheaper, like pine and the handles were plain and were usually made of iron. Any decorations would have been made of thin sheet tin rather than brass. The cheapest coffins would be completely undecorated and have rope handles.

Shrouds and coffin linings were another way of showing wealth. When Park Street opened in 1810 most ordinary people would be buried in a shroud made from woollen flannel fabric. This was because of a law called the ‘Burying in Woollen Act’ which wasn’t repealed until 1815. This law was designed to protect the British wool trade from imported fabrics like linen. The rich could pay a fine if they wanted to bury their dead in other fabrics, and so fabrics like linen, silk and even cashmere were used for shrouds to show the status of the deceased. This fashion continued long after the law was repealed.

The preservation of coffins and coffin furniture at Park Street is variable across the site. In many cases the iron coffin nails and handles have become ‘concreted’ which means their original shape can’t be easily seen, and the wooden part of the coffin has rotted away leaving only a stain in the soil.

There are several cases where breastplates have survived but because the names are painted onto the lacquered surface, or inscribed lightly into the metal, they are not always legible. Below are two relatively well-preserved examples. In both, the breastplate is shaped like a shield.

However, in a few cases there is good preservation of the coffins, particularly inside vaults, so we can see the coffin furniture and coffins clearly. One of the most striking aspects observed is that many are ‘fish-tail coffins’ which taper in at the ankles before flaring out again. These are produced by making shallow saw cuts in the boards to allow them to be bent into a curve.

Before the Park Street excavation this shape of coffin was not known to be common in Birmingham because they were not noted in previous archaeological excavation of burial grounds, for example the dig at St Martin’s-in-the-bullring. They had been seen in some other parts of the UK, click here for an example found in Blackpool.

There are several theories as to why fish-tail coffins were used, including the idea that the tightness of the coffin at the ankles made it difficult for resurrection men (grave-robbers) to steal bodies. Resurrectionists often tunnelled into graves at an angle, opened the end panel of a coffin at the head end and dragged the corpse out. This meant that graves would not look like they had been disturbed. Another theory is that this shape simply became fashionable because one or more of the local coffin makers had moved into Birmingham from an area where this was already a commonly-used shape for coffins, eventually making the style popular here too.

We know that in the 19th century most coffins were made by undertakers. Undertakers were often carpenters, cabinetmakers or upholsterers by trade, who did undertaking as a side-line. They would buy the coffin furniture from a company like Newman Brothers, but make the coffins themselves. Sometimes they would hire other trappings needed for the funeral and procession, like the hearse and black feather plumes for the horses. These were sourced from ‘funeral furnishing’ companies, these big firms had huge warehouses, full of everything they might need. In Birmingham the largest company was Ingle, Parsons and Clive, whose headquarters were in Digbeth, not far from Park Street.

If you have enjoyed reading my blog and would like to learn more about coffin fittings, how they were made or the lives of the Brummies who ‘made a living out of dying’ at Newman Brothers, please check out the Coffin Works digital archive or visit the museum which is open Wednesday – Sunday (plus Bank Holiday Mondays) for guided tours on the hour from 11am to 3pm. Admission is by guided tour only. Click here for more information or to book tickets.

The archaeological programme at Park Street in Birmingham is being carried out by our experts on behalf of LM for HS2 Ltd. To find out more about the programme visit https://www.hs2.org.uk/ or for information on what is going in your local area or how you can get involved head to https://hs2inbirmingham.commonplace.is/.

Explore the archaeology programme on social media with #HS2digs.

Want to read more about our archaeologists have found in the HS2 Park Street excavations? Click here to read about the Hidden History of Birmingham in our previous post.