Stories from Horsemonger Lane Gaol

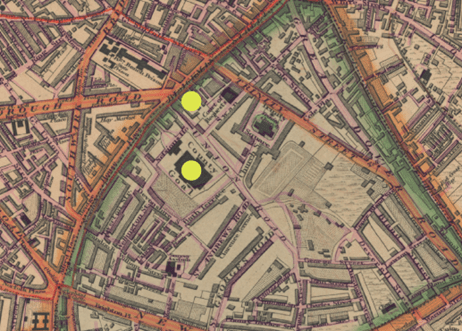

These stories from Horsemonger Lane Gaol are presented as part of the King’s Place development, Southwark. We're carrying out archaeological work at King's Place on behalf of Arcadis and Unite Students.

Horsemonger Lane Gaol

The Surrey County Gaol, commonly known by the name of the road it was built on - Horsemonger Lane, is now the leafy Newington Gardens, located just behind King’s Place on the opposite side of Harper Road.

The gaol (jail) opened in 1798 and closed in 1878. During this time, Southwark was part of the county of Surrey.

This was one of Georgian and Victorian London’s most notorious prisons. Thousands of prisoners passed through its gates every year, and some never left. 126 public executions were carried out on the prison roof, with enormous crowds gathered outside the walls to watch.

Tragically many of the prisoners we know most about were executed, this is because accounts of their arrest and trials were reported in the press.

Conditions in the prison were not pleasant, even when it was newly built. In a letter written in 1798, Catherine Despard described how her husband Colonel Edward Despard was kept in:

“a dark cell, not seven feet square, without fire, or candle, chair, table, knife, fork, [or] a glazed window”, where “his feet were ulcerated by the frost”.

As well as prison and trial records, we can find out about many of the people imprisoned at Horsemonger Lane Gaol from the often sensationalised newspaper reports of their arrests and trials, and their very public executions. These executions were attended by thousands of people from across the capital, including the author Charles Dickens who was shocked by the crowds who attended, describing them as:

"a sight so inconceivably awful" - Charles Dickens to the Editor of The Times, Letters. Nov. 13, 1849

Leigh Hunt

Leigh Hunt was a poet who founded a radical journal called the Examiner with two of his brothers. The journal advocated for many political causes, including the abolition of slavery.

In an article published in 1812 “The Prince on St Patrick’s Day”, Hunt attacked the unpopular Prince Regent (later King George IV) calling him

“a corpulent gentleman of fifty... a violator of his word, a libertine over head and ears in debt and disgrace... the companion of gamblers”.

The Prince Regent sued Leigh and John Hunt (the journal's other editor) for libel. Leigh was sentenced to two years in the Surrey County Gaol, while his brother was sent to Coldbath Fields Prison in Clerkenwell. They were also fined £500, the equivalent of around £25,000 today.

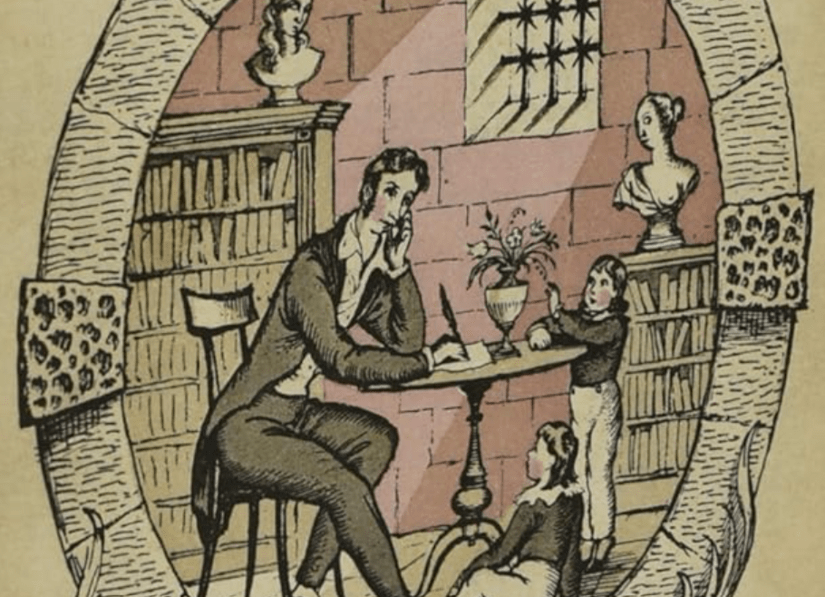

Leigh Hunt’s experience in prison was very different from most other inmates. He continued publishing both political pieces and poetry, and even was allowed to call in decorators to paint and wallpaper his cell, which one visitor described as being like

“something not seen outside of a fairy tale”.

Leigh’s wife and children regularly visited, as did friends and colleagues including the poets Keats, Byron, and Shelley. Hunt held dinner parties in his cell and played battledore – an early form of badminton.

Marie Manning

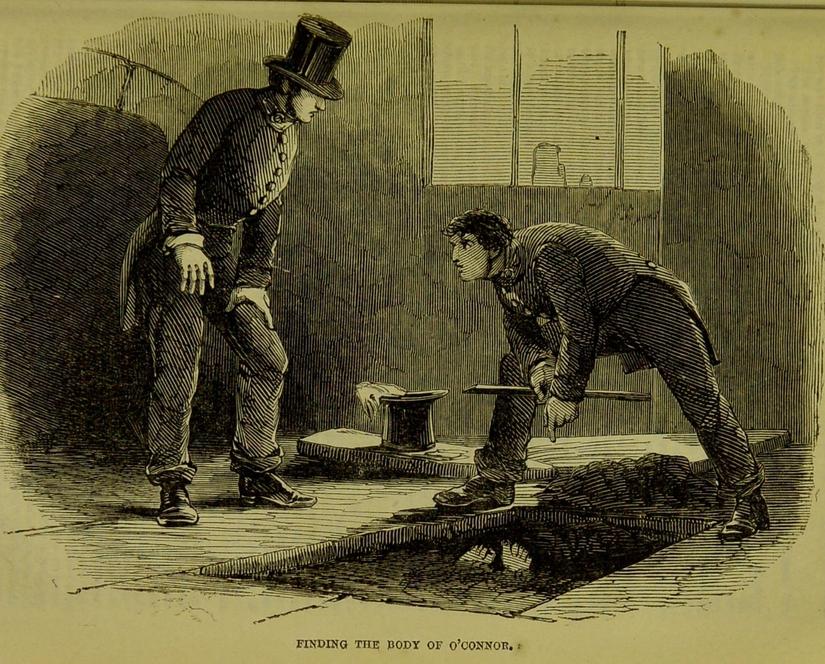

Marie Manning married her husband Frederick thinking he was an heir to a vast fortune. This fortune had been overestimated and eventually, Manning renewed a previous relationship with a man called Patrick O’Connor. In an incident nicknamed by the press as the “Bermondsey Horror”, Marie and her husband conspired to murder him for his money.

Marie invited O’Connor to dine at their house, which he had also done the week before. However, when he arrived they killed him using a gun and a crowbar. The Mannings buried O'Connor under their kitchen floor.

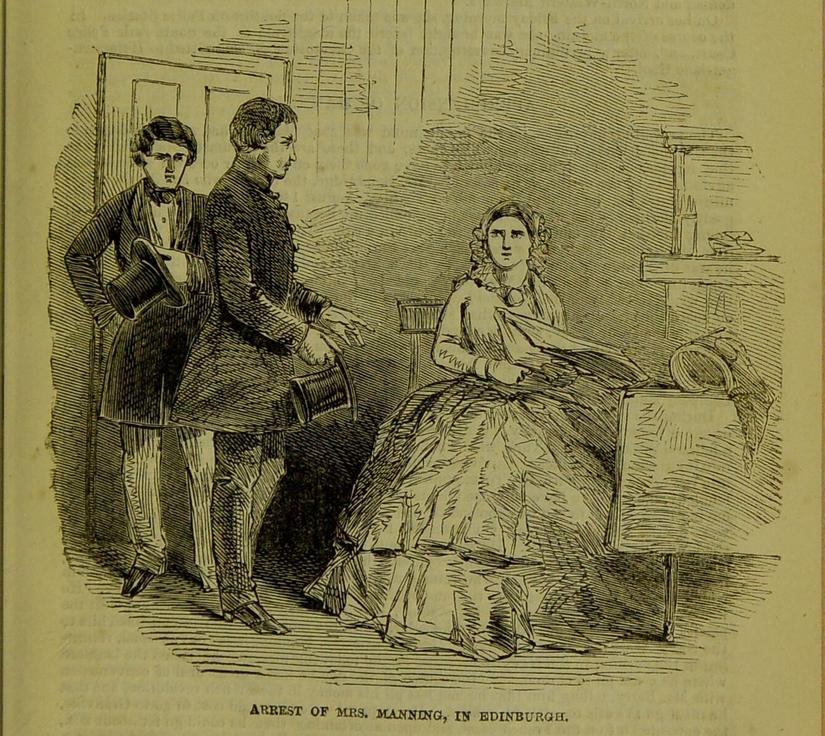

Marie then broke into O'Connor's house to steal his money and shares in a railway company. The couple fled separately - Marie was arrested in Edinburgh, while her husband was found in Jersey. According to reports, the crowbar was found at Lewes Station near Brighton.

The couple blamed each other at their trial and according to reports were not reconciled by the time of their joint execution. Dickens attended the execution at the Surrey County Gaol on the 13th of November 1849. He later included Maria Manning as a character (the lady’s maid Hortense) in his novel Bleak House.

A full account of the trial was published in 1849 and is illustrated with a number of sketches.

Sarah Herring

Sarah Herring was executed with her husband in 1806 for high treason after they were caught coining – clipping coins to make counterfeit money. They claimed their equipment was for making bird cages.

Unlike UK currency today, many coins in the early 1800s were made with a percentage of precious metals. In fact, until 1820 many pennies were made with silver, and anything over a half-guinea was made with gold. This meant by clipping small pieces of the edges of these coins you could melt them down with other metals and create your own fake coins, which you could easily pass off as real.

There was a lot of skill involved. Coin clippers not only had to make sure they were using the right amounts of different metals to make a convincing fake, but they also had to be confident enough to use the fake coins to pay for goods and services. However, for many it was worth the risk. Wages were low in 1806, with many earning under £50 a year (equivalent to around £2000 today).

Counterfeit coins were made in England for centuries, and thousands were arrested, imprisoned, or, as in the case of the Herrings, executed for it. Coining was considered treason because coins had the face of the king or queen on them.

Captain Henry Nicholl

Captain Henry Nicholl (or Nichols) was sentenced to death in August 1833 for what the judge described as “abominable” crimes – his relationships with other men. He had been on the run since friends helped him escape arrest the previous November.

Nicholl had been a captain in the army and fought in the Peninsular War, a conflict between Spain, Portugal, and Britain 1807-1814. One of the friends who helped him escape arrest was Lieutenant Thomas Beauclerk, who may have served with him. Beauclerk was arrested at the time and died in Horsemonger Street Gaol in December 1832.

One newspaper report contained a copy of a letter Nicholl wrote before his execution, including the line

“let not those who survive me flatter themselves that all of guilt of mankind goes to the gallows”

According to another report, as Nicholl was led to his execution, he stopped to thank the prison governor for treating the prisoners with “tenderness and humanity”. The same newspaper tells us that his family did not claim his body. Instead, like many executed prisoners in the 1700s and 1800s, his remains were sent to a local hospital for surgeons and anatomy students to dissect and study.